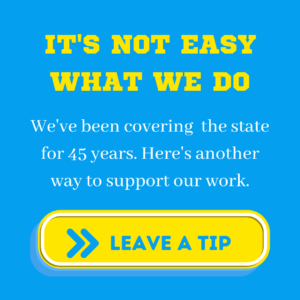

San Jose Leland grad & former NFL safety Pat Tillman (left) is shown as a corporal for the U.S. Army Rangers. World War II veteran and former Liberty of Brentwood head coach Jack Ferrill is shown displaying photo at his house in Stockton in 2017. Photos: Wikipedia.com & Mark Tennis.

On Memorial Day, especially in 2020 in the middle of the Coronavirus pandemic, it’s time to remember those who’ve fallen. For us, it’s not just those who’ve died in military service, but it’s also about remembering those veterans who lived long and prosperous lives. One of those we got to know, World War II veteran Jack Ferrill, passed away at age 93 just last December.

Note: We hope you enjoy this free story on CalHiSports.com. We just did our Super 65 All-Time Greatest Football Teams feature in five posts for Gold Club members only and will have a lot more Gold Club features prior to the upcoming fall (which is looking like will have some kind of a season). This includes Class of 2022 Hot 100 player rankings and a list of every undefeated team (at least five wins) in state history. None of this is available anywhere else. For more on special offer to get signed up for $3.99 for one month, CLICK HERE.

Note: This article is taken from our book “High School Football in California,” published in August of 2018 by Skyhorse Publishing of New York. The 20-chapter book can still be purchased through this link at Amazon.com.

There are many players observed over the years who have been fiercely competitive and focused at a razor-sharp level. And then there was Pat Tillman from Leland High of San Jose in 1993.

In recruiting terms still used today, he’d be called a tweener. Too small to be a linebacker and not fast enough to be a defensive back. But the way he played the game — with intelligence and great instincts to go with that intensity — created interest from some colleges and he signed a letter of intent with Arizona State.

For anyone who remembers seeing Tillman play, he’s a blueprint for that type of player, one whose competitiveness and immense internal engine simply stands out on every play.

After helping Leland win a CIF Central Coast Section title in 1993, Tillman headed to Tempe and his story after that is well-known. He became an All-American strong safety for the Sun Devils and went to the NFL with the Arizona Cardinals in 1998. As his pro career was beginning to blossom in 2002, Tillman gave it all up to join the U.S. Army Rangers and then in April of 2004 he was killed in Afghanistan in what later it was learned was a friendly fire incident. He was 27 years old.

Today, Leland High plays at Tillman Stadium and in September of 2017 a 400-pound bronze statue of Tillman was unveiled at Sun Devil Stadium in Tempe.

That kind of praise for Tillman’s sacrifice is deserved, but he’s far from alone. There have been no doubt hundreds if not thousands of former football and former athletes from California high schools over the years who have given their lives serving their country.

Leland High School dedicated football stadium several years ago to the memory of Pat Tillman. Photo: waymarking.com.

In the early 1960s, La Habra High in Orange County had an outstanding two-way player, Steve Joyner, who later became a promising defensive end at San Diego State after playing for two years at Fullerton Junior College. According to an article in the San Diego Union-Tribune in 2017 about a book “Promise Lost: Stephen Joyner, the Marine Corps and the Vietnam War,” Joyner gave up his SDSU career in 1966 to join the Marines. Then in 1968, while defending a hill near Khe Sahn in Vietnam, he was shot and killed. One of Joyner’s coaches at San Diego State was defensive coordinator John Madden, the former Super Bowl winning head coach of the Oakland Raiders and legendary NFL commentator.

In the Afghanistan war that began shortly after September 11, 2001, it was reported in a Los Angeles Times article in 2010 that Buchanan High of Clovis had more former students killed as soldiers in that war (seven) than any other high school in the state.

Two of those soldiers played football for the Bears for their team in the 2000 season that won the CIF Central Section Division I title. Jared Hubbard, 22, died in action in 2004 from a roadside bomb while Nick Eishen, 24, perished on Christmas Eve in 2007.

The Hubbard family also lost another son and a brother of Jared’s when Nathan Hubbard perished in a helicopter crash earlier in 2007.

When the family of Nick Eishen couldn’t find his football championship ring for his burial, former Buchanan coach Mike Vogt gave them his ring and Nick was buried with it.

Who Wouldn’t Jump For Jack?

The other life stories among those who played high school football and then joined the military are about those who returned. Some of them who went to World War II benefitted from the GI Bill and became influential teachers and coaches.

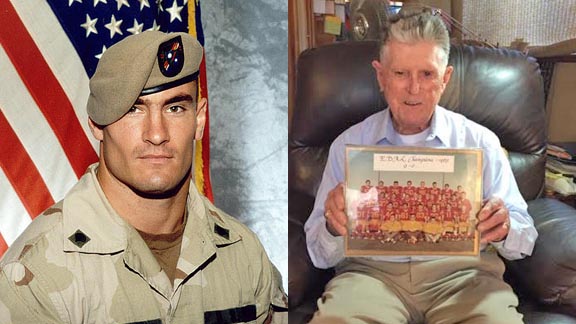

Perhaps one of the best examples of someone who did that is Jack Ferrill, who at age 91 during the 2016-17 school year was still teaching physical education two days per week at a high school in Brentwood, which is in Contra Costa County. And he began teaching and coaching in 1951.

Ferrill, who died in the fall of 2019 at age 93, became an interview possibility for our book “High School Football in California” after he went to an all-star football game in Tracy in June of 2017. It was a particularly hot, summer night and Jack simply went through the entrance to the stadium and walked slowly but with purpose to a seat in the bleachers. Due to the weather and since he was by himself, there was at least enough concern to approach him and ask him a few questions.

Yes, getting him some water would be nice. Yes, he drove from Stockton to Tracy for the game on his own. Yes, he still went to games during the season. And he was okay to state his age. Then after learning he was a World War II veteran, played for the 1943 undefeated Stockton High Tarzans and was a coach for more than 50 years, a more formal interview was arranged.

As a player, Ferrill recalled playing in the line for Stockton High. In those years, meaning from the late 1930s and into the early 1940s, the Tarzans were among the best in the state. Their unique nickname was derived from the Edgar Rice Burroughs book. No other high school in California before or since has used it, either. The only reason the Tarzans don’t exist today is that Stockton High itself closed in 1957.

“I went there from 1941 to 1944 and those were great years,” Ferrill said. “I was actually a swimmer and a football player and enjoyed both tremendously.”

The Tarzans had an undefeated and untied team in 1938 at 9-0 that is still listed in the Cal-Hi Sports Record Book as State Team of the Year. When Jack played there, they were unbeaten as well in 1943, although there weren’t that many schools in the state during the war years that played that many games. That team, coached by Larry Siemering, won three of its first four games by shutout, then topped Sacramento High 39-6. The final win was 34-19 over Grant of Sacramento.

“That was a team that just would not be beaten,” he said with the same bravado that many kids have today when talking to the media. “We never were really in trouble in any of our games.”

After he graduated, Ferrill joined the Marine Corps. The war was close to concluding, but he wanted to help in any way possible.

“No doubt that playing football helps in the military,” Jack stated. “It’s because you’ve already had some discipline. The first thing that happens is there’s a sergeant in your face at boot camp with his finger in your face. I was able to take that I think because of football.”

Ferrill didn’t serve in a combat unit but was in an infantry unit and eventually settled into a role of being an orderly for superior officers. He went to Japan and served in various roles for the U.S. occupying forces.

“Actually, you wouldn’t believe how nice the Japanese people were to us in those days,” he said. “Their cities and everything else was just blown apart and they were very courteous. I think maybe they were still afraid. But it was kind of amazing.”

After being discharged, Ferrill went to Stockton Junior College and then used benefits of the GI Bill to get degrees from the University of Pacific. Jack says he didn’t pay one penny to go to college.

“That’s the greatest thing since sliced bread,” he declared of the GI Bill. “It was just a beautiful thing the government did for all of those soldiers. It made up for the time lost for all of us and it got us a lot of good leaders.”

Coaching became a future profession for Ferrill when he was still in college. A local high school, St. Mary’s of Stockton, was struggling and needed some help. Jack helped. In the last game of that season, the Rams tied Edison of Stockton and Ferrill was hooked.

Our book was published in August of 2018.

After graduating from college, Ferrill used other connections from Pacific to land a job as a physical education teacher and assistant football coach at Liberty High in Brentwood, which is a 30-minute drive west of Stockton.

For the next 13 years, Jack assisted Liberty varsity head coach Lou Bronzan. Ferrill was there in 1956 when the Lions featured one of the best players in Northern California, a versatile running back who also kicked field goals and extra points named Herm Urenda.

Urenda was selected to the 1957 North-South Shrine All-Star Classic, which in the 1950s before pro football became popular was one of the biggest football events every summer in Southern California. The 1957 Shrine game also came on the heels of the 1956 season in Southern California when two running backs at different schools — Randy Meadows of Downey and Mickey Flynn of Anaheim — seemed to capture the imagination of everyone.

With Meadows and Flynn both on same team from the South, the expected large crowd arriving to watch at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum was way beyond what the Shriners were expecting. Estimates are that it was 85,900. It’s still the largest crowd to ever witness a California high school sporting event and it’s a record that is safe to say will never be broken.

Jack Ferrill was one of those who was there that night. His main objective was simply to see how one of the players he had coached at Liberty might look in an all-star game like that. Urenda not only looked good, but he was the MVP after he led the North to a stunning 32-0 victory with 101 yards rushing, two touchdowns scored plus kicking points.

“I was thrilled to death,” Ferrill responded when asked what he thought of that night. “I got to meet a lot of the kids, too. Herman scored all those points. Here was this kid from the little town of Brentwood who stole the show.

“It was strange in a way to be in a crowd like that. But some of the people around us started cheering for Herman when they found out who we were.”

Ferrill became the head coach at Liberty in 1963 and he remains that school’s winningest coach in its history. The Lions finished 9-0 in 1965 and in 1969 also went unbeaten.

By 1973, Ferrill’s career took a turn to the administrative side. He served in roles such as physical education chair, athletic director, vice principal and principal until he retired in 1990.

That retirement, however, only lasted approximately two weeks until the opportunity to help out at Independence, a continuation high school in the same district at Liberty, became available.

In addition to teaching at Independence until shortly before his death, Ferrill also had been serving as president of the Stockton Athletic Hall of Fame and the Liberty Joint Union High School District Hall of Fame.

“A high percentage of the kids I coached played later at state universities,” Ferrill said. “I was proud of them because they never gave up. What more can a coach ask for?”

Ferrill still goes back to his military roots when thinking about many of his former players and students.

“There were two wounded in World War II from our 1943 team,” he remembered. “We also had one kid (at Liberty) who was killed in Vietnam. He was a door gunner on a helicopter that crashed.”

During the 2016 football season, Ferrill saw Freedom High of Oakley play several times during its 10-0 regular season and in the CIF Northern California Division 1-AA regional championship. He also was very happy in 2017 when Liberty won the 2017 CIF North Coast Section Division I crown, the school’s first-ever section title.’

“I’m always proud of kids from the district and love to be cheering them on,” he said. “I got a call just yesterday from someone who was commenting how much I influenced him as a teacher. That’s what it’s all about.”

Mark Tennis is the co-founder and publisher of CalHiSports.com. He can be reached at markjtennis@gmail.com. Don’t forget to follow Mark on the Cal-Hi Sports Twitter handle: @CalHiSports